From the Old World to Chicago: 1872-1880

Moritz Karpen brought with him to America a great ambition-–a cherished dream. —Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association. “The Story of Karpen.” Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, August 26, 1930.

In the decades after the 1830s, immigration from Prussia to America grew. Usually, single young men and, to a lesser extent, single young women left for America. Christians also left as family groups to take up farming once again in America. Sometimes, a poor Jewish family or widow/widower would leave for America when they had no viable economic opportunities. In 1872, more than 8,000 people emigrated. [1]

Moritz and Johanna Karpen’s situation was really very unusual. Moritz in 1872 was 48 years old and owned a cabinet-making business with real assets. Although serving in the Prussian army had been a obligatory service for Jews for a century, their eldest son was only twelve years old during the Franco-Prussian War. Fear of conscription was not an imminent concern. Moreover in the small towns no anti-Jewish events occurred in 1872 that would have pushed them to leave.

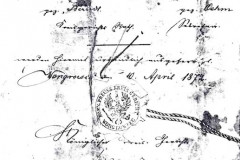

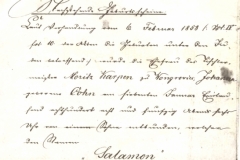

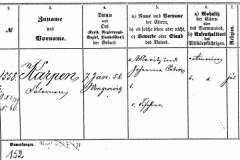

Whether it was just the “dream” or more basic forces at work, on April 10, 1872, the Karpens’ emigration papers were signed by the Prussian District Court, Wongrowiec. Each person’s permission to leave included his birth date as inscribed in a specific volume and page, and his parents, Moritz Karpen and Johanna born Cohn.[2] The Karpens carried these emigration papers with them to America.

With eight children under twelve, the usually difficult journey must have been incredibly more challenging. Often ship manifests show that extended families made the trip together, but the Karpen family seemed to have been alone.

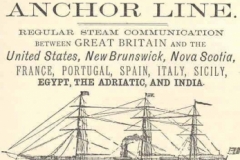

Like other immigrants, the Karpens would have taken a train from Wongrowitz to Posen and then another train trip of several days to Bremen or Hamburg. While most immigrants took ships from Bremen or Hamburg to New York, about one-third of the immigrants undertook indirect immigration. The Karpens came by indirect immigration. They could have taken a ship to an English port and then traveled by train to Glasgow, Scotland; or they could have taken a ship directly to Glasgow. Just less than two months after their emigration papers were signed in Wongrowitz, the family boarded their transatlantic ship, the SS California.[3]

The SS California was a steam-ship built by Anchor Line, a Scottish company. [4] The ship measured 361.5 ft. x 40.5 ft x 24.2 ft., with 7 bulkheads, 2 decks, and a 1047 HP engine.[5] It was superior to the earlier Anchor steamers and could accommodate 150 in Saloon, 80 Intermediate and 700 Steerage.[6]

The advertised rates of passage between Great Britain and New York were between ₤12 and ₤16, “according to accommodation and situation of Berths.”[7] This price would not have included food; children under 10 usually traveled for free. Perhaps Moritz and Johanna chose to travel via Glasgow to make the arduous trip on a new ship, or perhaps the trip cost less than leaving via a German or French port.

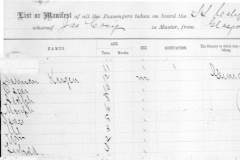

When the SS California departed on June 15, 1872 on its maiden voyage,[8] the ship’s manifest included the Karpen family. The Anchor Line relied heavily on steerage passengers from Scotland, and also from Ireland as it stopped in Moville, the port of Londonderry. Scandinavians took ships across the North Sea to Glasgow to board transatlantic ships.[9] On the June 15th voyage, most of the passengers were Scottish, Irish, or Scandinavian, and 20 German. Moris Kargen [sic], a joiner, was one of the few craftsmen.[10] The handwritten manifest listed: “Salman Kargen [sic], 12; Oscar, 10; Adolph, 8, Menph.[Benjamin], 6; Isaac, 5; M. [Michael], 3; Wm. [William], 2; Leopold, 10 [?] [months].” The additional manifest family information included: all male; all from Germany; all going to US. [11] The shipmaster, Captain Jason Craig, signed the manifest.[12]

The passage took two weeks. On board the ship, their parents tied the boys to each other so they would not fall overboard.[13]

On June 29th, 1872, the Karpen family arrived in America at New York Castle Garden,[14] which was the entry point before Ellis Island opened in 1892.

The Karpens’ Unusual Path

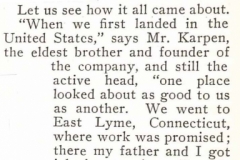

By the 1870s, most immigrants would join family or friends who had already settled in America. Once again, the Karpen family took an unusual path. The eldest son Solomon recalled with amazing simplicity what must have been a very trying time for the family[16]:

The family would have taken a train journey of several days to reach Chicago. Once again, uprooting and moving their large family must have been difficult.

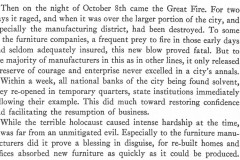

The Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association years later confirmed the Karpens’reasoning behind their decision to move to Chicago: [17]

After the fire, the population of Chicago was ca. 367,000. In 1873 with sixty furniture manufacturers in business in Chicago,[18] the employment prospects were very favorable for good cabinet-makers.

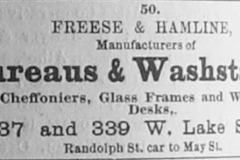

Once there, the family really settled in. Moritz, “Morris,” as he sometimes was called in America, immediately got a job as a carpenter.[19] He worked for the furniture manufacturing firm of Freese and Hamline.[20] The company produced “medium-grade chamber sets,”[21] manufacturing a “full line of bureaus, bureau frames, and washstands.”[22] The family lived at 481 North Franklin in the section Near North Side of Chicago.[23]

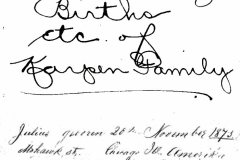

During their first year in Chicago the family’s connection to America strengthened. On November 20, 1873, the last of the Karpen children—the ninth son, Julius —was born on Mohawk Street. Julius was the only native-born child and always received special treatment.

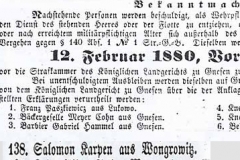

In February 1873, the family’s remaining financial tie to their home in Wongrowitz was cut when their house and factory was sold.[24]However, the Prussian government in Wongrowitz listed Solomon in the local newspaper in 1880 a draftee who must appear for conscription. Also the government included the Karpen young men in a register organized by date of birth of boys of age to serve in the military into the 1880s. The register included each boy’s birth, his parents, where he was living “America” and his religion “Jewish.”

All the boys (except Solomon who was already working) attended Chicago public schools where they learned English. [25] Solomon could only attend night school.[26] A love of baseball was an immediate attraction to the active and athletic growing boys. Isaac “Ike” attended Wells Public School. Michael “Mike” was in school until the sixth grade. According to family lore, Mike and William “Will” were in the same class. The teacher got after Will, bawled him out for doing something, and supposedly it was not justified. She sent Will home. Mike got up and went home too. And that was the last time the school ever saw Mike.[27]

In 1873, and continuing throughout the next ten years, the older boys became apprentices, but not all of them in the furniture business. Adolph, at 13, apprenticed to the druggist Gustave Mueller, with a view to learning the business where he remained for five years.”[28] He was promoted to clerk at 17[29] and boarded at his parents’ house.[30] Adolph began studying at the Chicago College of Pharmacy in 1878. Benjamin at 13 began working as a cigarmaker and continued in the trade.[31][32] He lived at 74 Fremont.[33]

In 1877-8, Morris “Maurice” [sic] was a carpenter[34] and rented at 28 Emma St. (now West Cortez St.) in Northwest Chicago.[35] He “established himself in a modest way in the upholstering business,”[36] and in carpentry and furniture making in 1877-8.[37][38] For a few years his business was located at 9 Cornell and was listed in the Chicago Business Directory of the Lakeside Chicago City Directory.[39] The family also lived at that address.[40]

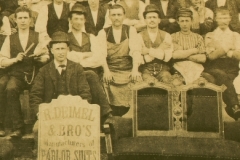

Morris “apprenticed his two eldest sons [Solomon and Oscar] in a larger establishment, where they could acquire an all-around knowledge of the trade, always under the inspiration of his own mastery of the craft.”[41] Solomon was already a skilled cabinetmaker so when he was 17 in 1875 “he hired out as an upholsterer’s apprentice to gain the extra experience;”[42] [43] he earned $3.00 a week.[44] [45] He was first employed by McDonough, Price & Co., A. C. Schmidt, R. Deimel & Bro. and others of the pioneer manufacturers of Chicago. [46]

Solomon recalled that “It was not the money I was after right then; it was the knowledge. A man who knows nothing of a steam engine may be able to pull some lever that will start it, but he may have a hard time in saving the thing from destruction once it gets started.”[47] Solomon lived at 48 Fremont and then rented at 124 W. Division.[48]

In 1879 both Solomon and Oscar worked for the upholstery and manufacturing company, R. Deimel & Bros., started by three brothers who were Jewish immigrants from Austria. A member of the Deimel family lived near the Karpens on Emma Street.[51] The company was located at 205 Lake St.[52] and later at Canal and Mather Streets.[53] Solomon was an upholstery cutter.[54] Oscar was a gilder,[55] the craft of applying gold leaf to ornate furniture.

Solomon left Deimel Bros. and went to Kansas City, Missouri for about a year[56] where he was a foreman in an upholstering plant,[57] the Kansas City Parlor Furniture Company.[58] “Until he was twenty, [Solomon] gave all his wages, except a little he kept for spending money, to his mother. After age twenty, in 1878, however, he was his own man….”[59] He probably earned about $50 a month. [60] He came back to Chicago from Kansas City in the fall of 1880, [61]

In 1872 Moritz and Johanna were members of a Jewish community in a Prussian town with their sons’ futures as small-time cabinet-makers pre-ordained and secure. Less than ten years later, the family was now living in the growing city of Chicago with their sons’ prospects unknown but extremely promising. Those years were the foundation of creating their American Dream… and Moritz’s Dream.

- State Archive Posen, Landrats Wagrowiec (Findbuch Nr. 338, 1815-1918); sygnatura 62; 23-03-1874 str. 45-48; Deutsche Auswanderer-Zeitung, Bremen, March 23, 1874p # 45- 48. ↑

- Emigration Document. Wongrowitz, Germany. (Private collection, Emily C. Rose). ↑

- Ira Glazier and P. William Filby, eds., Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving in U.S. Ports, Vols. 1–31 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988-1996), Vol. 27, May 1872-July 1872, p. 330, listed under Kargen) . Ship Manifest, New York. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Micropublication M237. Microfilm Roll # 361; List # 676; Lines 16-23. National Archives, Washington, DC. LDS Film 017571 7. ↑

- Commander C. R. Vernon Gibbs, British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans: A Record of the British Passenger Lines and their Liners from1838 to the Present Day, (London: Putnam, 1963), 222-3. ↑

- www.norwayheritage.com ↑

- Commander C. R. Vernon Gibbs, British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans: A Record of the British Passenger Lines and their Liners from 1838 to the Present Day (London: Putnam, 1963), 227 ↑

- Commander C. R. Vernon Gibbs, British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans: A Record of the British Passenger Lines and their Liners from 1838 to the Present Day (London: Putnam, 1963), 224. ↑

- www.norwayheritage.com ↑

- Commander C. R. Vernon Gibbs, British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans: A Record of the British Passenger Lines and their Liners from 1838 to the Present Day,(London: Putnam, 1963), 222-3. ↑

- Ira Glazier and P. William Filby, eds., Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving in U.S. Ports, vols.1–31 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988-1996), Vol. 27, May 1872-July 1872, 330, listed under Kargen) . ↑

- Ira Glazier and P. William Filby, eds., Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving in U.S. Ports, vols.1–31 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988-1996), Vol. 27, May 1872-July 1872, 330, listed under Kargen) . ↑

- Ira Glazier and P. William Filby, eds., Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving in U.S. Ports, vols.1–31 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988-1996), Vol. 27, May 1872-July 1872, p. 330, listed under Kargen) . Ship Manifest, New York. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Micropublication M237. Microfilm Roll # 361; List # 676; Lines 16-23. National Archives, Washington, DC. LDS Film 017571 7. ↑

- Sis Stephenson, granddaughter of Mike Karpen. Interview with Emily C. Rose, 1994. ↑

- Ira Glazier and P. William Filby, eds., Germans to America: Lists of Passengers Arriving in U.S. Ports, vols.1–31 (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1988-1996), Vol. 27, May 1872-July 1872, p. 330, listed under Kargen) . Ship Manifest, New York. Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Micropublication M237. Microfilm Roll # 361; List # 676; Lines 16-23. National Archives, Washington, DC. LDS Film 017571 7. ↑

- Solomon Karpen in Neil Clark, “How Nine Brothers Built Up a $10,000,000 Business,” Forbes, Aug. 1, 1926, 9. ↑

- Neil Clark, “How Nine Brothers Built Up a $10,000,000 Business,” Forbes, Aug. 1, 1926, 9. ↑

- Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association: 50 Forward Years 1888-1938” (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, 1938), 2. ↑

- Per Schoff, S.S. The Industrial Interests of Chicago: comprising a classified list, with locations and brief description, capital invested, number of men employed, and amount of annual production, of the principal manufacturing establishments in the city (Chicago: Knight & Leonard, 1873) in Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association: 50 Forward Years 1888-1938 (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association 1938), 3. ↑

- Edwards Chicago City Directory, 1873, 535. ↑

- “Funeral Today on Coast for Mike Karpen,” Retailing Daily: Home Furnishings Newspaper, New York, July 3, 1950, 1. ↑

- Sharon Darling, Chicago Furniture: Art, Craft, & Industry 1833-1983 (New York: Norton, 1984), 98. ↑

- Trade Bureau, Mar. 1, 1884, 24. ↑

- Edwards Chicago City Directory, 1873, 535. ↑

- Stadtarchiv Wagrowiec, Wagrowiec T. III-K. 263, Oct. 14, 1845- Feb. 10, 1873, p. 66. ↑

- John Leonard, ed., Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men of the City of Chicago (Chicago: Marquis & Co., 1905), 322. ↑

- John Leonard, ed., Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men of the City of Chicago (Chicago: Marquis & Co., 1905), 323. ↑

- Bill Winberg, grandson of Mike Karpen. Interview with Emily C. Rose, 1998. ↑

- Alfred Andreas, History of Chicago, 1871-1885. Vol. 3. (Chicago: 1884), 550. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8,577. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8,577. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1875-6, 554. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1879, 599. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1875-6, 554. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8, 577. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8,577. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., Makers and Designers Distinctive Furniture (Chicago, S. Karpen & Bros., 1918), 1. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8, 547. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1879, 599. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8, 1185. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8, 547. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., Makers and Designers Distinctive Furniture (Chicago, S. Karpen & Bros., 1918), 1. ↑

- “16,500 Furniture Workers: S. Karpen Factories,” The Southern California Forum (Mar. 11, 1949): 4. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1876-7, 563. ↑

- S. Karpen, “How to Become a Millionaire,” Worker’s Magazine, Feb. 25, 1912, 5. ↑

- Lakeside Chicago City Directory, 1875-6, 554. ↑

- Furniture Journal, Oct. 9, 1908, 121. ↑

- S. Karpen, “How to Become a Millionaire,” Worker’s Magazine, Feb. 25, 1912, 5. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1876-7, 563. ↑

- [Photo] Karpen Komment (Sept. 1926), 26. ↑

- [Photo] Letter by Leo Karpen, Mar. 1, 1948. Private Collection, Sis Stephenson, Granddaughter of Mike Karpen. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1877-8, 319. [Ignatz, Liquors] ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1879, 330. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1880, 336. ↑

- Karpen Komment, Sept. 1926, 26. ↑

- The Lakeside Directory of Chicago, 1879, 599. ↑

- Karpen Komment, Sept. 1926, 26. ↑

- Neil Clark, “How Nine Brothers Built Up a $10,000,000 Business,” Forbes, Aug. 1, 1926, 9. ↑

- Furniture Journal, Oct. 9, 1908, 121. ↑

- Neil Clark, “How Nine Brothers Built Up a $10,000,000 Business,” Forbes, Aug. 1, 1926, 9 . ↑

- Per Schoff, S.S. The Industrial Interests of Chicago: comprising a classified list, with locations and brief description, capital invested, number of men employed, and amount of annual production, of the principal manufacturing establishments in the city. Chicago: Knight & Leonard, 1873. in Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association: 50 Forward Years 1888- 1938 (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, 1938), 3. ↑

- Furniture Journal, Oct. 9, 1908, 121. ↑