The First Karpen Building on Michigan Avenue: 1892-1893

Chicago is acknowledged to be the greatest market for upholstered goods in the country and it can be safely said that the Karpen Bros. line is one of the very best of the many shown in it.— American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, February 4, 1893, 18.

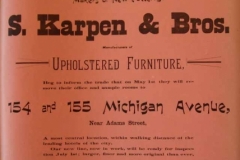

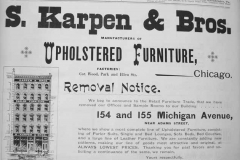

Karpen Bros. moved to rented premises on Wabash Avenue in 1889. “During the preparations for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, however, rents increased and it was necessary, due to an ever expanding distribution [sales] to find another location.”[1] Solomon, Oscar and Adolph made a potentially risky business decision. In spring 1892 they purchased a six story building at 154-155 South Michigan Avenue at the corner of Adams Street (After 1908 this address became 122-138 Michigan Ave.).[2] [3]

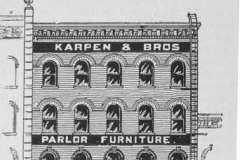

During those years, Michigan Avenue was not “The Mich. Boul.” of later decades. Nevertheless, ownership of a building on the important thoroughfare was quite an achievement after only twelve years in business and twenty years in America. Seeing their family name on the facade must have been special indeed!

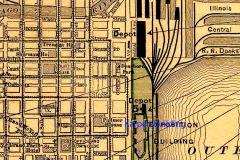

Karpen Bros. knew the meaning of the saying, “location, location, location” as the key to getting the necessary traffic of buyers to its showrooms. As they advertised, the new showrooms and offices were most centrally located, within easy walking distance of all [transportation] depots and ten of the leading hotels.[4][5] And the trade press took note: “the central location of its show room make it very easy of access to buyers.”[6]

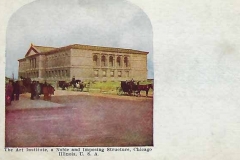

The brick building, erected in 1889, was located near important Chicago landmarks— the Art Institute and the Auditorium. It was directly at the rear of a large new retail furniture store . [7] The building fronted 39 feet on Michigan Avenue by 171 feet deep, six stories and a basement.[8]

The company remodeled the building at an expense of about $10,000.[9] New passenger and freight elevators[10] were installed, and electric lights [11] produced a well-lighted establishment.[12][13] It required four floors to show its full line.[14] “From their upper floors a beautiful view of the lake can be had and the shipping on the outer harbor.”[15]

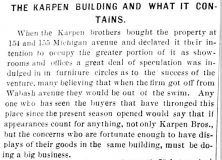

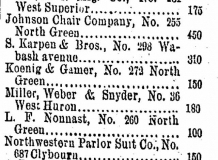

The trade newspaper, however, reported that “a great deal of speculation was indulged in furniture circles as to the success of the venture, many believing that when the firm got off from Wabash avenue they would be out of the swim.”[17] Karpen Bros. immediately took action to remedy that problem: they brought the furniture trade to their new site. The trade papers instantly applied the name “The Karpen Building” to the new building which added caché to the location. Then Karpen Bros. sought out substantial furniture companies to rent quarters and offered more reasonable rents than other landlords. Rapidly the building was nearly “filled with good, live furniture men and will be a place visited by the trade coming to this market as frequently as any of the downtown show-rooms, and any one looking for a central downtown location cannot do better than … to secure quarters in this building before it is too late.”[18]

Within a year, skepticism changed to unabashed praise. Trade press reporters described in detail the new showrooms and Karpen Bros.’ line:

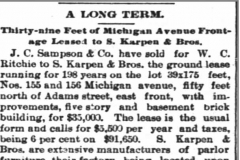

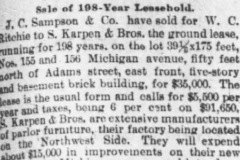

Just a few years later, a furniture trade journal wrote that the company had made a very sound financial decision. Solomon, Oscar, Adolph and their wives[19][20] “secured a big bargain in this purchase,” [21] and a “ridiculously low rental”[22] At the time the ground lease was valued at $100,000.[23]

“Makers of New Patterns” drew attention to its plethora of styles it brought out each year. The trade papers embraced the phrase: “they have certainly maintained their reputation as makers of new patterns;”[24][25] they are indeed “Makers of New Patterns,” as indicated in their advertisement. [26]

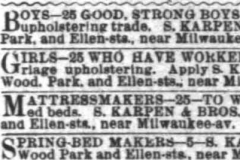

Not surprisingly, labor and union matters were on-going issues for the management of Karpen Bros., other furniture manufacturers, and the newly-formed Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association. The problems they faced had been brewing for decades: a ten-hour day and higher wages for piece work as the union claimed that the average wages paid to upholsterers in the United States was less than $2 a day. [27] The International Upholsterers’ Union, formed in 1850, the Carvers’ Union, the Teamsters’ Union, the Furniture Workers’ Union, and other unions represented the workers in Chicago’s furniture industry. The bloody Haymarket Affair [the Haymarket massacre or Haymarket riot] of May 1886 in Chicago was sparked by a demonstration for the eight-hour day. That demand and the demand for an increase on piece work were unresolved.

When Karpen Bros. and other furniture manufacturers faced a major labor problem in 1892, they responded to it under the umbrella of the Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association with Adolph in a leadership position. The International Upholsterers’ Union had 2,000 members, 50 per cent of the entire number of men engaged in that trade. There were 800 upholsterers in Chicago, and 650 of these, it was claimed, were members of the organization.[28] A furniture trade journal reported that there were 1,200 members of Upholsterers Union in Chicago.[29] The International Upholsterers’ Union met in secret session in August 1892 in Chicago setting out its demands for shorter hours and a uniform scale of wages. [30] The union threatened to strike in a month or so. [31]

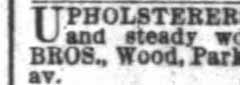

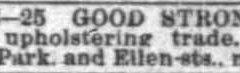

Since the Karpen factory employed more than 250 workers (although not all of them upholsterers), it was one of the largest, if not the largest, employer of upholsterers in Chicago. At the beginning of November, the Upholsterers’ Union presented a scale of wages to Karpen Bros., which they asked to be adopted by them. The refusal caused the Union to order their men out on a strike. [33]

Karpen Bros. reacted to this threat two-fold. It hired non-union men to fill those positions as rapidly as possible, [34]and it opened a factory in Milwaukee. Adolph explained that decision to a trade paper: “We have rented the four-story and basement building, formerly occupied by Carpele’s trunk factory on 6th street near Grand avenue [Milwaukee] and shall commence operations there at once. We expect to have a force of upholsterers there by next Wednesday…. We have been thinking of making a move of this kind for some time for a number of reasons, the principal one is the labor question, which is more or less an unsettled condition here most of the time and is a constant source of annoyance to people engaged in the furniture trade.”[35]

Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association set up a committee to deal with the situation and met with the union. The trade paper reported what then occurred: “The Union demanded that the first thing to be done was for Karpen Bros. to discharge every non-union man they now had, which was met with a flat refusal. They would not consider any proposition unless this step was agreed to, so that the Karpen Bros. factory is now being run with a non-union force. The committee of manufacturers has, with a great deal of labor and after a number of meetings, made up a scale of wages which all have agreed to adopt December 1st. The schedule covers all classes of work and is considered eminently fair in every way, and it is thought that the men in the shops outside of Karpen Bros. will not refuse to work under it, and it is hoped that the strikers will see that it is to their best interest to do likewise before their places are all filled.”[36]

As soon as the strikers learned that Karpen Bros. had started the Milwaukee factory with all non-union men, they set up committees, and, according to Adolph, made a number of threats. [37] Karpen Bros.’ Milwaukee factory was running and shipping orders for two weeks[38] when it was destroyed by fire. “So rapid did the flames spread that the workmen narrowly escaped with their lives and one foreman of the finishing room was burned to death.” [39] A fireman suffocated while fighting the blaze.[40] The loss of the factory was valued at $34,000 with $11,000 covered by insurance.[41] The events were covered by the Milwaukee and Chicago press as there were other suspicious fires in those days. Adolph responded to the events by stating that while “the origin of the fire could hardly have been other than incendiary, he maintained that his firm had no clue to the guilty person. We do not wish to be interpreted as placing it at the door of our striking employees, and the only possible way in which an imputation of this kind could be made is the fact that two members of a committee from our Chicago strikers who went to Milwaukee Saturday, November 19th, departed Tuesday morning for home. It is, however, significant that our Milwaukee house [factory] was carefully watched by us day and night and the fire started in our building.” [42]

The strike spread to every upholstery factory in Chicago as the union rejected the uniform scale of wages for piece work. [43] They also demanded, to no avail, that its union be recognized. Six weeks after the strike began, “the Upholsterers’ Union at a meeting by 300 of its members last night at Greenebaum’s Hall, declared their strike off.”[44] The set-back for the Upholsterers’ Union[45] was caused by “by the decided stand taken by the manufacturers, through the perfect organization they had. Under the new order of things each shop [factory] is allowed three men on day work, all of the balance working piece work.”[46]

While we might condemn this treatment of workers, in the late 19th century, Karpen Bros. dealt with labor in the manner of the times. We will see that as the times changed in the 20th century, so did the management-labor dynamic.

- Carl Saunders, “They Called Us Crazy, but ─,”[An Interview with Sam Karpen] Furniture Manufacturer, September, 1930, [1]. (reprinted by S. Karpen & Bros, “Karpen Celebrates Half Century of Service.”) ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Mar. 19, 1892, 18. ↑

- Furniture Journal, Oct. 9, 1908, 121. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 7, 1892, 23. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Apr. 9, 1892, 28. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Jan. 7, 1893, 45. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Mar. 19, 1892, 18. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 7, 1899. ↑

- Trade Bureau, June 28, 1892, [3]. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Feb. 4, 1893, 18. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, Aug. 13, 1892, 13. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Apr. 9, 1892, 28. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, July 9, 1892, 17-8. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, June 25, 1892, 26. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 21, 1892, 14B. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, May 21, 1892, 23. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Feb. 4, 1893, 18. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 28, 1892, 20. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 17, 1899.↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 17, 1899. ↑

- Furniture World, Jan 19, 1899, 35. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, June 28, 1892, [3]. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan. 8, 1899. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, July 9, 1892, 17-8. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker & Upholsterer, Aug. 13, 1892, 13. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Jan. 7, 1893, 45. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 14, 1892. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 14, 1892.↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec.10, 1892, 14. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 14, 1892. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 14, 1892. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., Karpen Komment, Mar. 1928, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 26, 1892, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 26. 1892, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 12, 1892, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 26, 1892, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 3, 1892, 16. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 26, 1892, 15. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 3, 1892, 16. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Dec.29, 1892, 1. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Dec. 29, 1892, 1. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 3, 1892, 16. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 10, 1892, 14. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Dec. 13, 1892. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 17, 1892, 14. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Dec. 24, 1892, 15-16. ↑