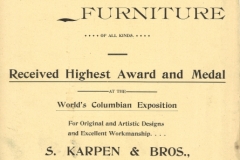

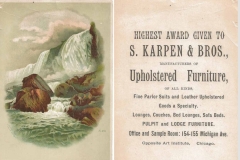

First Prize at The World’s Columbian Exposition—

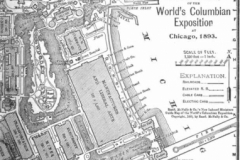

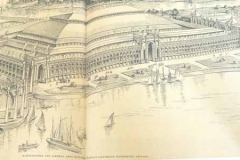

Chicago World’s Fair: 1891-1893

In this greatest display of fine furniture garnered from every corner of the globe, a Chicago manufacturer, S. Karpen & Bros., carried off first prize for design, workmanship, and finish. —Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association. “Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association: 50 Forward Years 1888-1938.” Chicago: Furniture Manufacturers Association, 1938, 10.

The growth of the Chicago furniture industry from 1880 to 1890 was dramatic and impressive. The statistics, variable by which furniture sectors were included, illustrated that growth:

| Chicago | 1880 Census | 1890 Census |

| No. Manufacturers | 198 | 157 |

| Capital | $2,919,626 | $10,536,349 |

| No. of Employees | 5,462 | 8,295 |

| Wages paid | ||

| Value of Material | ||

| Value of Product | $7,447,289 | $13,582,350 |

(Official Manufacturers Census Reports, The Trade Bureau, June 17, 1893, 4.)

Furniture, July, 1893, 13.

| Chicago | 1891 Census |

| No. Manufacturers | 270 |

| No. of Employees | 20,000 |

| Value of Product | $25,000,000 |

(American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 23, 1891, 15; June 20, 1891, p. 31; June 27, 1891, p. 9.)

In 1890, Chicago’s value of product surpassed New York’s by nearly $100,000.[1] Nevertheless Chicago, compared to New York and Grand Rapids, was still looking for its place as a leading furniture market. Adolph Karpen was one of Chicago’s foremost promoters. In a speech to his fellow manufacturers, he chastised them and pointed out that Chicago’s furniture output of its 250 manufacturers was more than $22,000,000. He boasted, “Other markets have the specialties, but Chicago makes everything.” Instead of talking too much of their city, the Chicago manufacturers have talked too little. They are to-day too modest. “The growth of the furniture manufacturing industry has kept pace with the growth of the city and that is one of the marvels of the century.”[2]

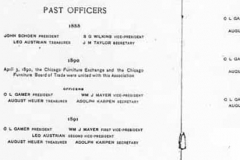

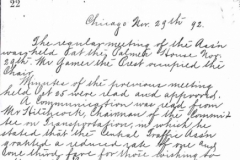

Adolph did not just talk; he believed in taking action. In 1891 he pushed the Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association to mount a furniture exposition since “he believed that the time was ripe for Chicago to declare herself.”[3] He served as secretary of the Chicago Exposition Committee”[4] that planned the event held in the Inter-State Exposition Building with 240,000 square feet of floor space. Secretary Adolph Karpen announced that “about 130 firms altogether will have spaces on the floor….Some manufacturers who were at first luke-warm or opposed to the project are now anxious to make exhibits, now no room is left for them.” [5]

Karpen Bros. seized the opportunity to raise its profile and created an impressive display. Mike and Ben Karpen and Sig Fish were in charge of sales at the exposition. A trade journal wrote: “… and it is safe to say, ‘They are in it:’”

The opening ceremony took place in the center of the Exposition Building from a handsome booth decorated with streamers and bunting. The Chairman of the Executive Committee, Mayor Washburne, and the ex-mayor spoke. [6]

The Official Program set the stage:

Only on Saturdays and in the evenings was the public given an opportunity to view the displays, swelling the crowds to an estimated 10,000 daily. [7] As reported in a newspaper, “They availed themselves of the opportunity to the number of thousands… an unbroken line of men and women kept wending into the Exposition Building and around the aisles between the various exhibits. The Chicago Orchestra, composed of thirty-five pieces, … discoursed music at brief intervals during the entire day.” [8]

With a self-assurance characteristic of the times, the executive committee asserted: “Considered either in detail or as a whole, the exhibition will stand unrivalled and unparalleled among the world’s trade expositions.” Both a souvenir booklet and a 132-page official program were issued. [9]

The Chicago Daily Tribune and The Chicago Post were effusive in their praise of the event as well:

At the conclusion of the exhibit, “two hundred and more of the furniture manufacturers of the city, with some of their friends, marched down from the Exposition Building to the Van Buren street pier and, followed by an inquisitive crowd of street urchins, boarded the steamer R. J. Gordon. The pleasure aboard grew as the boat steamed away, there being a banquet and a series of impromptu speeches.” During the four-hour excursion on Lake Michigan, Adolph Karpen, the chairman of the executive committee, and the City Attorney, “who had found his way aboard with a new line of stories, all ‘expressed their belief in the great advantage the exhibit had worked to the trade in the city.’” [10]

The reporters interviewed Adolph at length: “He stated that the average attendance had been about two hundred per day, and there was a surplus of about $1,200 in the treasury. During the four weeks of this exhibition the sales have amounted to not far from $1,500,000. The charge for space occupied was 5 cents per square foot, and with a rebate brings the cost down to four cents, which the committee considers a very satisfactory showing.” Adolph concluded that the success of the exposition had been much greater than anyone had anticipated.[11]

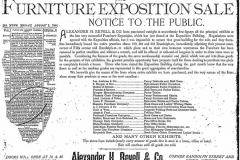

An important Chicago retail store owner bought $100,000 worth of furniture from the exhibitors, including Karpen Bros. “The purchase is said to be the heaviest ever made in the city.” [12] Alexander H. Revell & Co. rented extra space for his one-month Furniture Exposition Sale and advertised the event in the newspapers. Karpen Bros. pieces were listed as “Upholstered Library and Parlor Furniture.” [13]

Coming from this euphoric feeling of success, the furniture manufacturers had great expectations for the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition set to open in 1893. As early as 1889, the finance committee of Chicago World’s Exposition had invited S. Karpen & Bros. and eight other companies to a meeting “to aid in the efforts being made to secure the location of the World’s Exposition in Chicago.”[14]

Karpen Bros., not surprising, focused its efforts on the aspects of the exposition that directly impacted the company and Chicago furniture interests. In 1890 the mayor of Chicago spoke to the National Furniture Manufacturers Association which represented 2,000 furniture manufacturers. He assured the manufacturers that “you shall have as much space and as much facility as you may require to show all the people, not of Chicago, not of the Northwest, but of the entire world, what the furniture manufacturers of America can do in the art of its manufacture.” The National Furniture Manufacturers Association wanted the exhibit to be located in the main industrial building. There they should “exhibit on a grand scale… such samples of goods as are usually sold to the trade in order that foreign visitors may form an idea of the kind and quality of the goods made in this country.”[15]

Adolph Karpen served on committee to unite all the Chicago furniture manufacturers and retailers to ensure they would get a representative on World’s Fair Board of Directors. [16] Adolph Karpen and Alexander Revell were then selected by the committee to seek a seat on the Board. The vote taken resulted in seventeen votes for Mr. Revell and six for Adolph.[17] Since the furniture manufacturers bought $111,000 worth of stock in the World’s Fair, Mr. Revell was given a seat on the World’s Fair’s Board of Directors.[18]

While this sounded optimistic, the reality was decidedly pessimistic. “There is a great deal of dissatisfaction among [national] furniture manufacturers on account of their evident inability to secure sufficient space at the World’s Fair. No one now expects to get the amount of space desired or applied for, and the delay in knowing what is to be the allotment precludes in a great measure any preparations toward leading up an exhibit….”[19] In addition, it was still not announced by early November, that resulted in a “… growing spirit of indifference and will result in many instances in a refusal to exhibit.”[20]

The situation for Chicago manufacturers was more dire. The Manufacturers Building had limited space and more space available in the Education Building to be built.[21] There were too many applications for all buildings.[22] In addition, “Chicago, on this occasion, will be the host, and the World’s Fair Commissioners feel obliged to be more liberal with outsiders and prevent any appearance of the fair being monopolized by Chicago or being a local show…. The manufacturers need not lose their identity as small signs can be placed on the separate articles displayed. …good idea to arrange for a combined exhibit that would be representative and creditable to Chicago. …Space will be divided into rooms, and committees will arrange for all who will exhibit and plan out [the space] for the best [display]. This is to be a World’s Fair, and not a salesroom, as no sales will be allowed, and only manufacturers will be permitted to display.”[23]

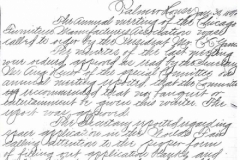

Adolph was from the beginning of the process involved with the Committee on the World’s Fair Exhibit.[24] In that regard, Adolph reported that Cincinnati, Grand Rapids, & Rockford intended to make a joint exhibit. He advised the Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association that he thought the best idea would be for a collective exhibit for Chicago that would exhibit in a way that the whole Chicago would make a creditable showing and appear to best advantage.[25]

As the opening of the fair approached, the ire of the potential exhibitors increased. It was reported that “20,000 feet is all that thus far has been set apart of furniture display, all told.” Indianapolis, Grand Rapids and Philadelphia formally decided to withdraw. “Cincinnati asked for 20,000 square feet and got 1,000, and so on throughout. It would appear that the furniture industry of the country is sadly left in the lurch, and perhaps necessarily so, because if every industry had the space it wanted Chicago itself would not be big enough to furnish room.”[26]

In the end, there was no collective exhibit of the furniture industry of Chicago at the World’s Fair, as was originally proposed. The gentleman [not Adolph Karpen] who had the matter in charge labored faithfully to secure sufficient space, but in vain. Thirty-two Chicago firms exhibited per The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition which varied from billiard tables to barber chairs to office and school furniture to piano stools. The other companies who did not exhibit cited reasons like they had not intend to so; their lines were not suitable for attractive exhibits; they were not able secure sufficient or any space, or they were not able or did not want to go to the expense.[27]

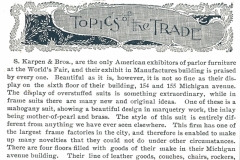

According to the trade newspapers, Karpen Bros., like many others, “did not secure as much space as they desired, but have accepted the inevitable gracefully and will make a creditable exhibit.”[28] “S. Karpen & Bros. are among the first to have their World’s Fair exhibit finished and in place. It is a very richly gotten up display of fine upholstering, showing a number of pieces in leather and fine silk fabrics, every piece being an original design which has been copyrighted.”[29]

“For a display of representative and specially artistic designs and workmanship in the upholsterers’ art, the exhibit of S. Karpen & Bros. at the World’s Fair certainly merits all the attention it is attracting, and the exclamations of admiration elicited from the sightseers, if heard by members of the firm, must fully repay them for all the trouble, money and time spent.”[30]

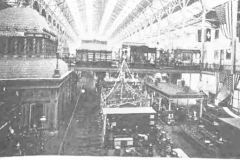

S. Karpen & Bros. exhibited Parlor Furniture in Section O-2, Booth 567 in the Manufacturers Building.

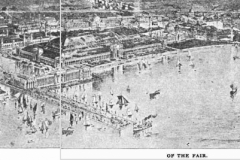

Once the fair opened, the naysayers proved correct. The trade newspapers did not sugarcoat the events in their numerous articles. During the May 1893 opening, “there were many visitors in the city to the opening exercises, and the furniture men, as a rule, entertained friends and customers who happened to have come to town. The weather has been unpleasant…” “Most of the American exhibits of furniture appear to be by Chicago houses. The Rockford exhibit has a rather small space.”[31] “The furniture man who can discover the least particle of benefit to be derived would be a rarity. The opening exercises and the visit of the President of the United States were the cause of many out-of-town people coming to town. But since that eventful day the city has been remarkably free from visitors, and furniture buyers are very scarce.”[32]

During June the attendance was light as rail prices were not lowered and the hotels continued with their high rates.[33] In the press, there was a general “roasting of management” regarding mismanagement and unfairness in dealing with exhibitors.[34]

“The furniture exhibits at the Exposition are slowly being installed. Judging from the present appearances, the furniture industry is not going to have a highly creditable display. A visit to any important retail furniture store would reveal a better showing. Absence of exhibits from manufacturers outside of Chicago, particularly by Eastern [ i.e. New York] concerns, is conspicuous. Many lines will not be shown at all.”[35]

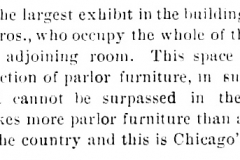

Against this dreary background, S. Karpen & Bros. shone. “One of the finest exhibits, and one having probably the best location, is that of S. Karpen & Bros., who have a corner stall, with good light. Their goods are beautiful and well arranged, and very creditable to this enterprising firm.”[36] “The firm [S. Karpen & Bros.] have one of the best exhibits at the Exposition.”[37]

On Chicago Day at the World’s Fair (October 9th), the furniture manufacturers closed their offices and factories and Karpen Bros. [and others] gave souvenir tickets to their men.[38]

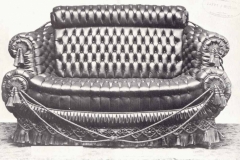

The Karpen display included: a Turkish rocker, a chair, a couch. a reception chair, a sofa, a divan, an arm chair, a rocker, two small chairs, and a library chair.[39] The Turkish style was in vogue, with the heavier more ornate pieces garnering greater public appeal. Most parlors photographed for interior decoration or style magazines and books showed at least one large Turkish piece. To insure the integrity of its designs, Karpen Bros. copyrighted some of the Turkish pieces. [40]

The construction of these Turkish pieces was special—the upholstery was placed on steel, not wood, frames. According to a later Karpen Bros. catalog: no tacks were used in the construction, but the work was only sewed; the entire foundation was built up with springs; the art of building up an artistic shape was the difficult portion of the work. As they claimed, nothing is the genuine Turkish work unless no wood or tacks enter into the construction of the back and arms.[41]

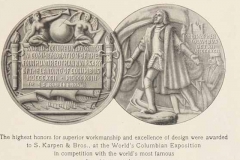

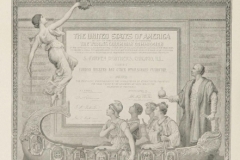

S. Karpen & Bros. won first prize for excellent workmanship in upholstery of overstuffed furniture.[42] “S. Karpen & Bros. were liberally treated by judges in the furniture department at the World’s Fair. They have as trophies of their artistic exhibit eleven medals, having received this number out of thirteen pieces shown by them. Surely with this as a result they cannot say that thirteen is a hoodoo number.”[43]

no images were found

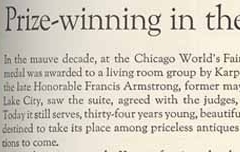

After the Exposition closed, the prize-winning pieces were purchased by the Standard Furniture Co., of Salt Lake City, Utah, and were resold to Francis Armstrong, who had been mayor of Salt Lake City from 1886-1890. In 1925, the suite was exhibited in Salt Lake City.Karpen Bros. told the same story in the text of a 1927 advertisement in Arts & Decoration. Mayor Armstrong’s house is listed in the National Register of Historic Places; the application stated: “carved woodwork and furniture purchased at the Chicago exhibition of 1893.”[44]

The six-month fair attracted more than 27 million visitors. Karpen Bros. took advantage of the location of the World’s Fair in its hometown to drive potential new customers to his showrooms:

In addition, “S. Karpen & Bros. have made great preparations to entertain the trade coming here this summer at their warerooms, which are very centrally located for visitors to the Fair, being opposite the new Art Institute and only a few steps from the depot and steamboat land of the direct lines to the grounds. It will be found to be a very handy place to make as headquarters, and the Karpen boys know how to make it pleasant for visitors.”[45]

The company continued to tout its prize in future publications and advertisements:

The Chicago World’s Fair propelled Karpen Bros. to the next plateau—a nationally-known company.

- Official Manufacturers Census Reports, Furniture, July, 1893, 13. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Feb. 7, 1891, 19. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 2, 1891, 21. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, June 27, 1891, 14. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, July 3, 1891. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, July 12, 1891. ↑

- Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, “Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association : 50 Forward Years 1888-1938,” (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, 1938), 9-10. ↑

- Chicago Daily Tribune, July 12, 1891. ↑

- Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, “Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association : 50 Forward Years 1888-1938,” (Chicago: Chicago Furniture Manufacturers Association, 1938), 9-10. ↑

- Chicago Evening News, Aug. 7 1891, in advertisement in Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 9, 1891. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Aug. 22, 1891) 18. Chicago Herald, Aug. 6, 1891. Also in 9 other papers. ↑

- Chicago Evening News, Aug. 7, 1891, in advertisement in Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 9, 1891. ↑

- Display ads, Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 9, 16, 23, 30, 1891. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Aug. 31, 1889, 17. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, June 21, 1890), n.p.; June 20, 1891, n.p. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Mar. 14, 1891, 12. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Apr. 11, 1891, 14. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 2, 1891, 21. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Oct. 15, 1892, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Oct. 22, 1892)n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Dec. 24, 1892, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Jan. 13, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Nov. 26, 1892, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, June 21, 1890, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Nov. 26, 1892, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Feb. 4, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Apr. 15, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, Feb. 18, 1893, n.p. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 20, 1893, 20. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, June 10, 1893, 40. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, May 18, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, May 27, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, June 3, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, June 10, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, May 27, 1893), n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, May 27, 1893, n.p. ↑

- The Trade Bureau, July 8, 1893, n.p. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Sept. 23, 1893, 13. ↑

- Typewritten list, World’s Columbian Exposition- 1893, Chicago History Museum. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Jan. 5, 1895, 14. American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Jan. 12, 1895, 46. American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Feb. 16, 1895, 71; American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Mar. 16, 1895, 15. ↑

- S. Karpen & Bros., The Karpen Upholstered Furniture Monthly 2 (June 1897). From the Collections of The Henry Ford Museum. ↑

- Chicago Upholstery Journal 2 (1897), 21. High Point Library. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, Nov. 11, 1893, 14. ↑

- Francis Armstrong House, National Register of Historic Places, May 23, 1980. ↑

- American Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer, May 6, 1893, 18. ↑